Pavilion III – sometimes called the Corinthian Pavilion – was the original home of the Law School, where the first law professors lived and taught classes. The pavilion was the second structure built in the Academical Village, preceded by Pavilion VII the year before. Construction began in June 1818, and Pavilion III was completed with the installation of its namesake Corinthian capitals in 1823. It is unclear precisely who was involved in the construction of Pavilion III during those years, though year-end expense accounts and other documents illuminate the central role of enslaved laborers in building the entire Academical Village. Among the individuals listed in the University’s receipts were enslaved workers who had been rented out to the University by their enslavers during 1818 and 1819, when most of the construction on Pavilion III took place.

When John Tayloe Lomax was hired to teach law at the University of Virginia in 1826, he moved into the completed Pavilion III with his family and a group of Black individuals he enslaved. Virginia personal property tax records in 1830 list Lomax in Charlottesville and as the enslaver of six people over the age of twelve, the age at which state taxes began to accrue. Like many of his contemporaries on the faculty, Lomax sought to expand his living quarters beyond the space allotted by the original pavilion structure. With permission from the Board of Visitors, Lomax hired George W. Spooner and William B. Phillips to build a kitchen structure along the north wall of the garden, adjacent to the pavilion. The outbuilding was completed around 1829 or 1830. Known as “The Mews,” the structure has undergone a series of expansions but is one of few outbuildings that remains standing in the Academical Village. For Lomax and following residents of Pavilion III, the Mews fulfilled two primary functions: expanding kitchen space and creating additional quarters for enslaved laborers.

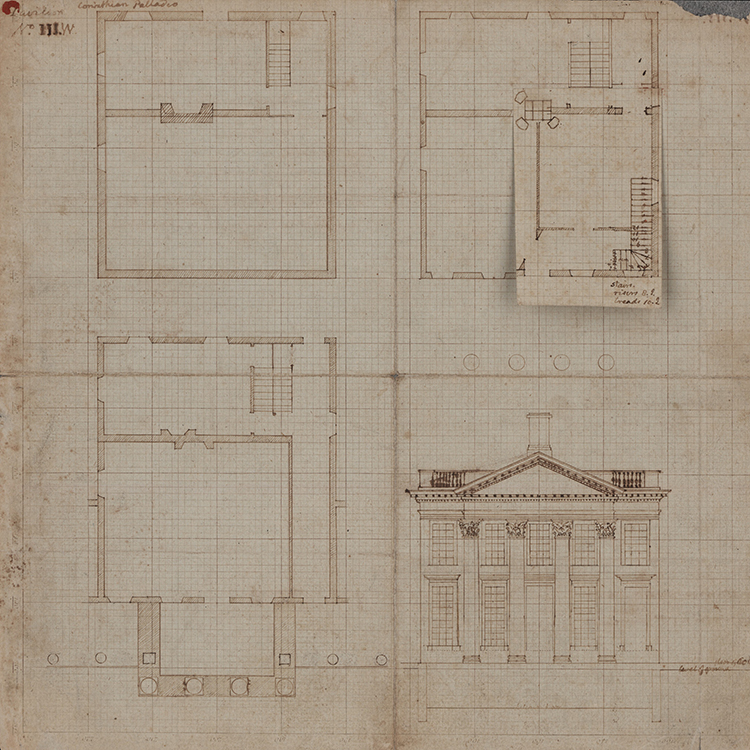

Professors both lived in and taught classes inside their assigned pavilions, and the design of Pavilion III reflects intentions to segregate the space and movement through it according to race. The pavilion had two entryways from the Lawn: one opening only into the lecture room, and the other connecting to the main hall and rest of the house. The second story, visible but not accessible from the Lawn, marked an additional space where the pavilion’s residents could surveil the Lawn, but which could not be accessed by students. Obscured by a panel in the main hall were the stairs to the basement, which included the kitchen and additional rooms for food preparation and storage. The basement, with its low ceilings, poor lighting, and notorious dampness, also served as sleeping quarters for enslaved workers. Outside Pavilion III and the Mews, the back garden served as a work yard in which enslaved people would have carried out tasks like tending and butchering livestock, operating the smokehouse, washing, and gardening, all of which were often labor-intensive, smelly, and loud. Despite architecture designed to separate students, family, and enslaved workers within the pavilion, the nature of these close quarters and records of professors’ and students’ complaints indicate that frequent disruptions and interactions were part of life in Pavilion III.

Following Lomax’s resignation in 1830, John Anthony Gardner Davis became UVA’s second law professor and moved into Pavilion III. With him came his family and a group of enslaved workers. While a professor at the Law School, Davis reported in the 1830 U.S. Federal Census that he owned 17 enslaved persons. These enslaved individuals may have lived and worked at the Davis family property, Lewis Farm, near the Rivanna River. Davis moved into the larger Pavilion X in 1833.

Pavilion III Gallery, created by the JUEL Project

Includes digital reconstructions and photographs of Pavilion III.