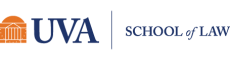

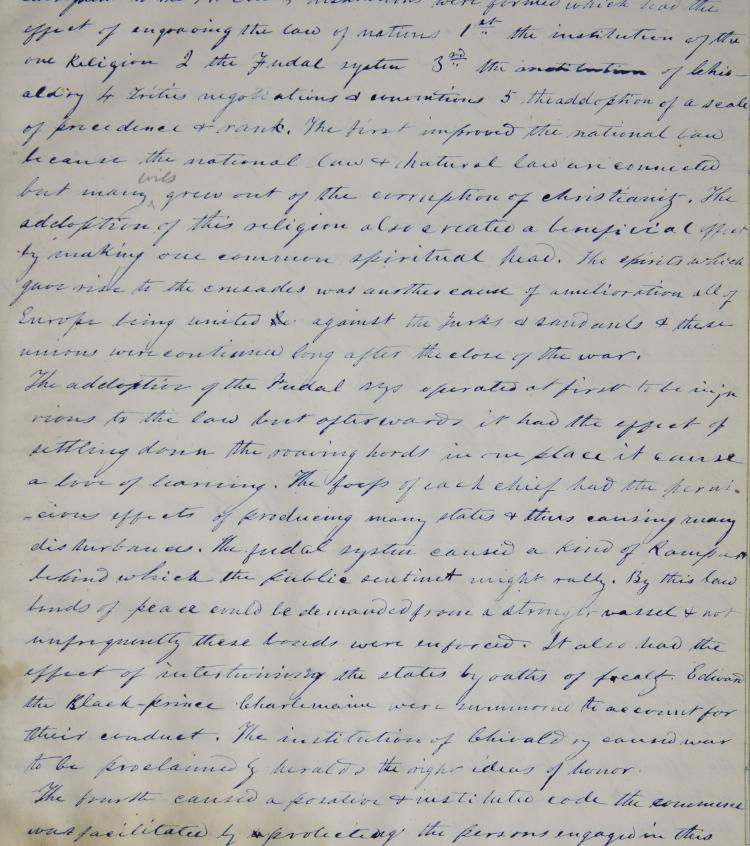

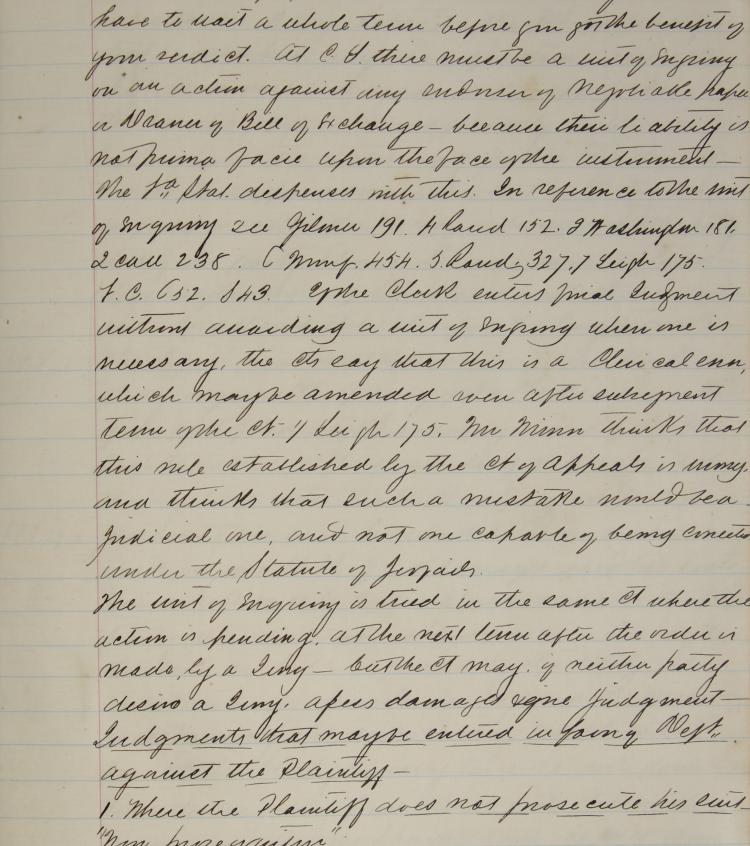

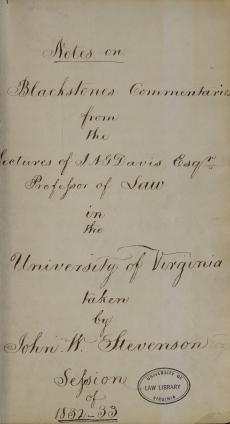

Notebooks kept by students enrolled at UVA Law make up the core of the Slavery and the University Virginia School of Law Project. Available here are digitized copies of student notebooks from UVA law courses before 1865. These student notes from faculty lectures are held at the UVA Law Library and offer glimpses of a legal curriculum that morphed over time according to the scholarly predilections of the Law School’s first faculty members and the broader national context of government and law. They also illustrate how Law School faculty and students brought the law to bear upon questions of property, contracts, and slavery.

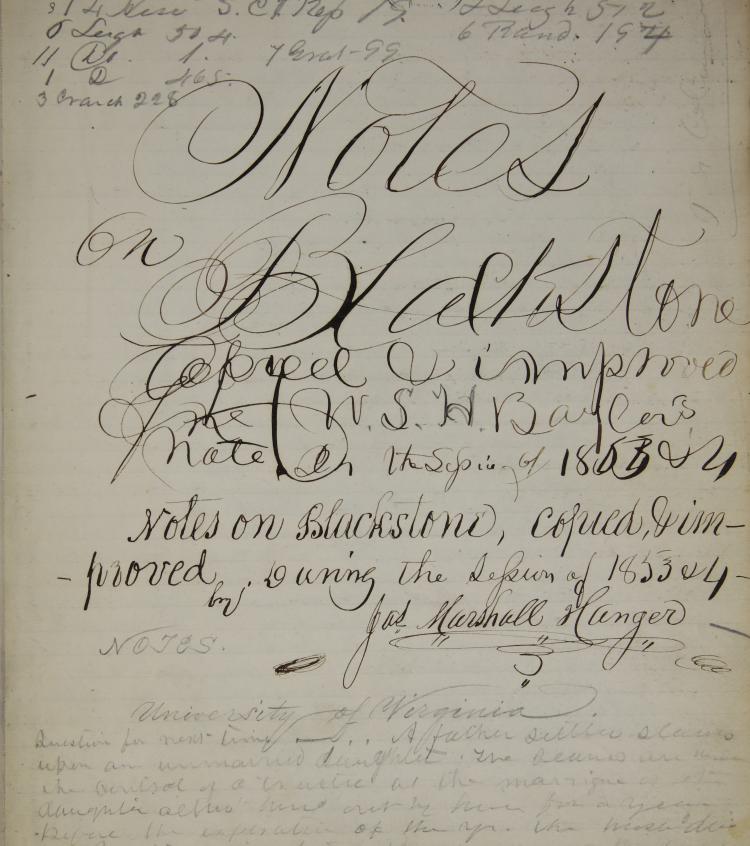

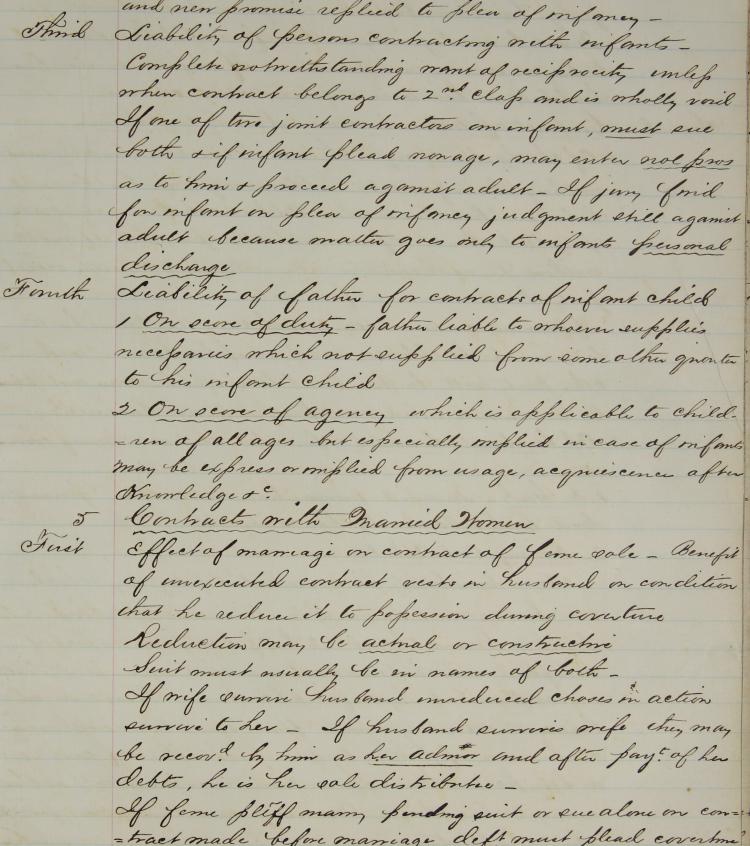

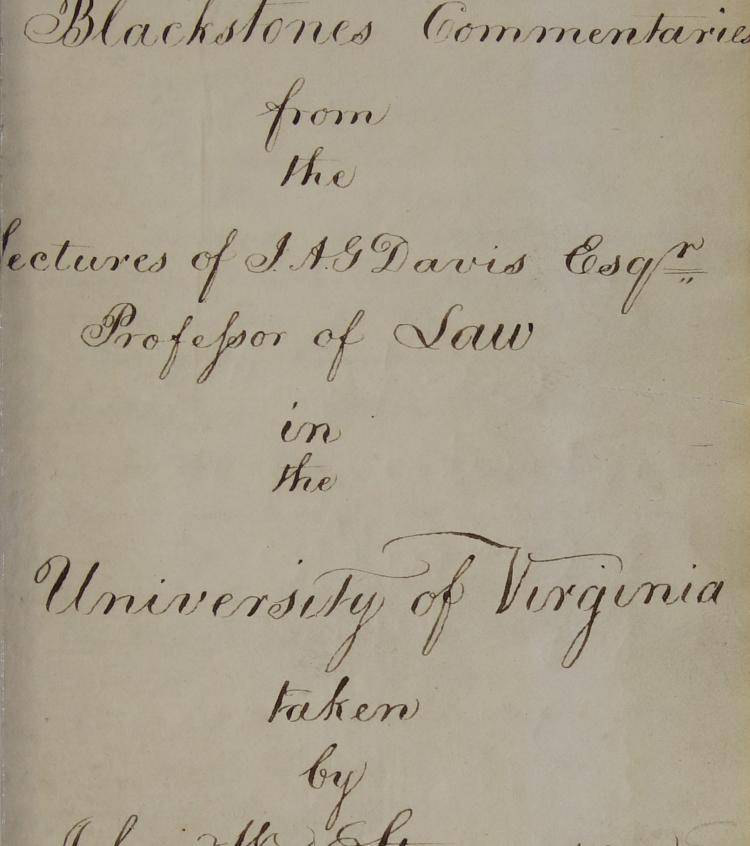

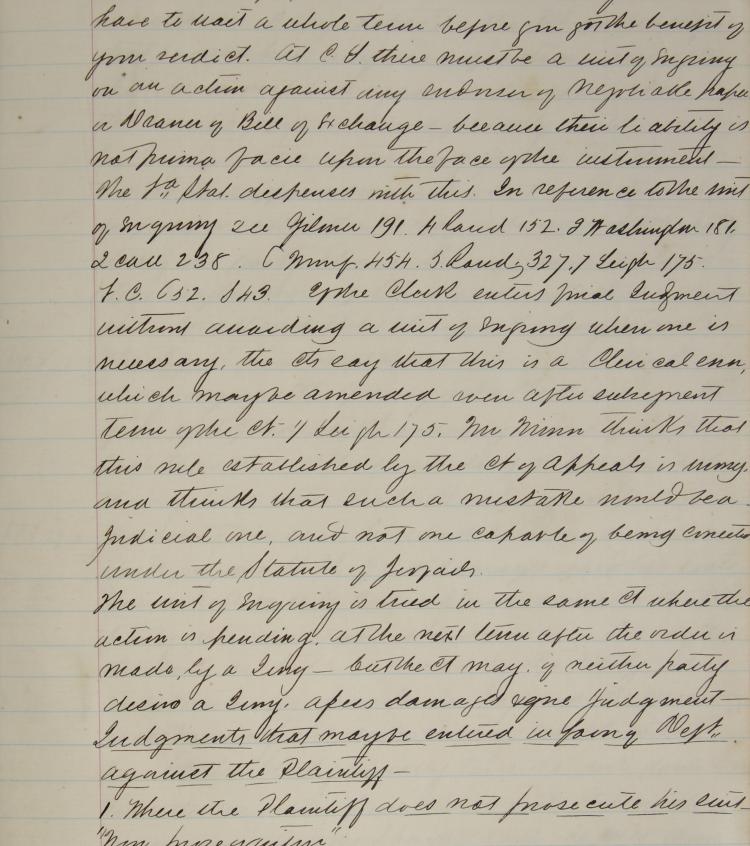

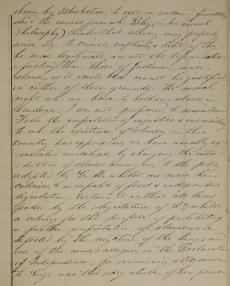

Student notebooks vary from one student to the next, although the content for classes such as John Minor’s Senior Law course tends to be consistent across notebooks. In the classroom, antebellum Law student notebooks show the legal curriculum to be heavily based in legal theory. The content contains consistent references to legal theorists such as William Blackstone and Emer de Vattel, which appear in parentheses by specific phrases and sentences along with relevant page or section numbers. It is often unclear whether a student is copying lecture notes or course texts verbatim, or when they are offering their own commentary. There are intermittent mentions of the professor’s perspective (i.e., “According to Professor Minor…”), but these are exceptional. Some content crosses over into the margins, with citations found there and the observation/lesson in the main body. Past student exams are occasionally located towards the end of a notebook (copied by hand rather than inserted separately), which may represent a shared camaraderie amongst law students of different classes. Pagination was typically added later by a different party and stamped on one of the top corners.

Class notes are both individual and “human” in their nature. Doodles, poems, witty retorts, financial scribblings, and other unrelated content are typically found in the front and backmatter, although these remarks and sketches can appear throughout. Some students were highly organized in their notetaking, being sure to copy down each word verbatim. Others were less structured and, as a result, the content can be difficult to follow.

Moreover, students often dedicated one notebook to several courses or had multiple notebooks for one course. In the former case, course chronology sometimes alternates between law and another subject like chemistry. These transitions sometimes occur abruptly and without explanation. In other notebooks, one page might have law notes while the back of the same page is dedicated to a different course. Furthermore, notebooks were occasionally shared with other students in which case more than one name was appended to a single notebook. Navigating these complexities is a key component of utilizing student notebooks as a historical source.

Given the importance of property law to the curriculum, slavery and enslaved people were part of lectures on debt liability, inheritance, and general conceptions of American law by implication, if not always by direct reference. While there are glimmers of cultural and political references, they are not predominant. Very rarely was an entire lecture devoted to the topic of enslavement; rather, professors interspersed the laws of slavery as well as theoretical interpretations of slavery throughout discussions on the U.S. Constitution and property law.

These lectures center on the rights of property-holding white men and their relationship to slavery and the state. Thus, Law School teachings provided the legal justifications for slavery—one important tool in solidifying a slave society—to students whose whole University experience nonetheless supported white supremacy and slavery.